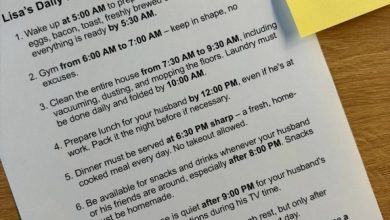

A depressed man walks into a bar and sits down!

ADVERTISEMENT

Thursday night at Murphy’s Tavern was the kind of quiet that made the neon beer sign sound louder than the chatter. A few regulars lingered, nursing drinks like they were part of the furniture. That’s when the door creaked open and a man stepped in — rumpled suit, tired eyes, shoulders heavy with something unspoken. He sank onto a barstool and gave the bartender a nod.

ADVERTISEMENT

Wiping down a glass, the bartender offered the usual opener. “Rough day?”

ADVERTISEMENT

The man sighed — the kind of sigh that could shake dust off the shelves. “You could say that,” he muttered. “Just found out my dad’s gay.”

The bartender raised an eyebrow but didn’t press. He’d heard stranger things. Life had a habit of sending stories through the door, wrapped in worn coats and quiet voices. He poured a double brandy, neat, and let the man sit with his thoughts.

The man stared into his glass, then emptied it in one long pull. He didn’t speak again that night. When he left, he left behind a silence that lingered like smoke.

Friday came. Same stool, same man — only worse. Shirt wrinkled, tie missing, eyes red. He collapsed onto the seat like gravity had given up on him. “Six double brandies,” he said without hesitation.

The bartender hesitated. “You sure?”

The man nodded. “It’s been a hell of a week.”

As he lined up the glasses, the bartender asked, “What happened this time?”

The man gave a bitter laugh. “Found out my son’s gay too.”

The bartender paused mid-pour. No words came. He just nodded and finished the lineup. The man drank them like medicine and left without a word.

By Saturday, the bartender was waiting for him — part concern, part curiosity. Just after nine, the door opened. Same man, same slump, same exhaustion. He held up three fingers. No words. Just the gesture.

The bartender poured.

After the sixth double, he leaned in. “I don’t mean to pry, but… does anyone in your family like women?”

The man stared into his drink, then gave a weary smirk. “Yeah,” he said. “My wife.”

The bartender froze, then burst out laughing before catching himself. The man chuckled too — just a little. But it was something. A flicker of life. He left a generous tip and walked out a little straighter. The bartender watched him go, wondering what kind of home he was heading back to.

A week passed. Murphy’s returned to its rhythm — same lights, same regulars, same country song stuck on the jukebox. Then another stranger walked in. Older. Weathered. Cowboy hat, dusty denim, boots that had seen miles. He tipped his hat and ordered a beer.

“What do you do for a living?” the bartender asked.

The old man grinned. “I’m a cowboy.”

“No kidding. Real cowboy, huh? What’s that like?”

He leaned back. “I work a ranch. Ride horses. Herd cattle. Fix fences. Mend what’s broken. Take care of the land, the animals, and the folks who live off it.”

“Sounds like honest work.”

“It is,” the cowboy said, sipping his beer. “Not easy, but good for the soul.”

A few minutes later, the door opened again. A woman walked in — tall, confident, the kind of presence that didn’t ask for attention but got it anyway. She sat beside the cowboy and ordered a cocktail.

The bartender smiled. “And what about you, ma’am? What do you do?”

She smiled back. “I’m a lesbian.”

The bartender tilted his head. “Interesting. What does that mean?”

She chuckled. “It means I love women. I wake up thinking about women, go through my day thinking about women, and when I fall asleep — still thinking about women.”

The bartender laughed. “Fair enough.”

The cowboy, quiet beside her, looked thoughtful. He finished his beer, tipped his hat to both, and left.

Later that night, he found himself in a smaller bar down the street. Quieter. More his speed. He ordered another beer. The bartender asked, “So what do you do, old timer?”

The cowboy took a long sip and said, “Well, this morning I thought I was a cowboy. But now I think I might be a lesbian.”

The bartender nearly spit out his drink. The old man didn’t flinch. Just smiled — like he’d figured out something the rest of the world hadn’t.

By closing time, both stories — the man with the family revelations and the cowboy with the identity epiphany — had become part of the tavern’s folklore. They’d be retold for months, then years. Some versions would be funny, others tragic. Some would turn philosophical, about love, identity, and the strange ways life unfolds.

The bartender, quiet witness to it all, knew the truth: bars aren’t just places to drink. They’re confession booths with better lighting. People come in heavy, drop their truths on the counter, and walk out a little lighter.

Some nights it’s heartbreak. Some nights it’s laughter. And if you’re lucky — it’s both.

That’s what makes the job worth it. The drinks change. The stories never stop.